Inside China’s Audacious Effort to Save a Dying Glacier

Updatetime:2025-05-28From:西北生态环境资源研究院

【Enlarge】【Reduce】

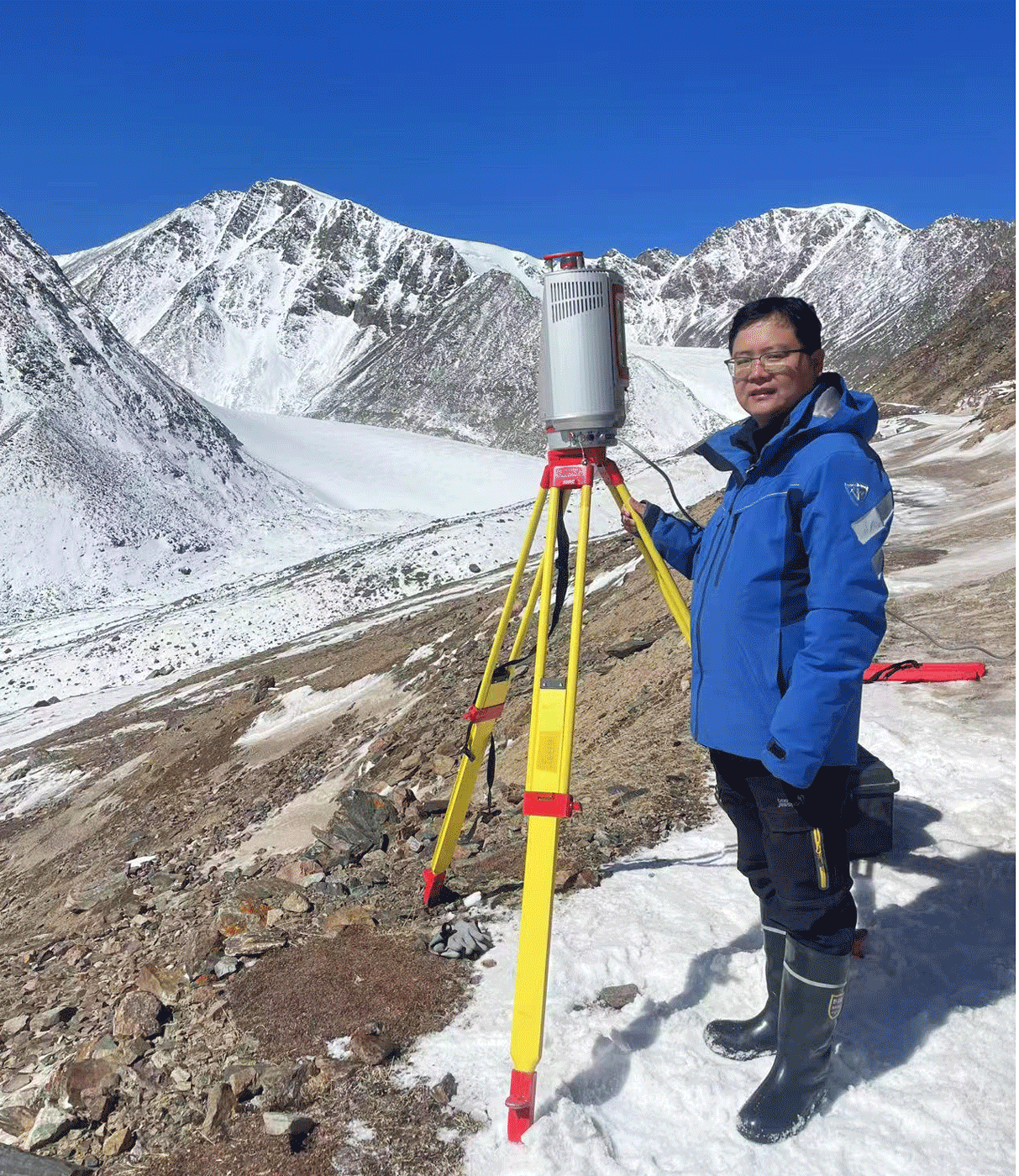

Glacier scientist Wang Feiteng has run the numbers, tracked the symptoms, and watched an ice sheet the size of 56 football fields shrink, year after year.

Everything points to one outcome: without urgent intervention, the Dagu Glacier will be gone by 2029.

“It’s like a patient with terminal cancer. No one can stop the inevitable,” the 45-year-old scientist from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in Beijing, admits. “But as the doctor, can you just walk away?”

So he returns each year to the mountain in an act of stubborn defiance: wrapping parts of the glacier in white, heat-reflective fabric; spraying artificial snow into thinning air; trying techniques borrowed from ski resorts and Olympic venues — anything that might slow the melt long enough to matter.

“With the limited funding and resources, we can’t treat every patient,” says Wang, who helped develop artificial snow systems for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics and now leads China’s most visible glacier project.

“Dagu Glacier is one of the most famous. We treat it in the hope that it might create a ripple effect,” he says.

Wang Feiteng at work atop a mountain. Courtesy of Wang Feiteng

Sitting on the eastern edge of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, Dagu ranks among the world’s lowest-elevation mountain glaciers, and among the most vulnerable of China’s 69,000.

The country holds roughly one-tenth of the world’s total glacier mass — yet between 2008 and 2020, its total glacier area shrank by 6%. Last year, Dagu became the only glacier in China added to the Global Glacier Casualty List, a UNESCO-backed project that identifies ice masses on the brink of disappearance.

That designation helped turn Dagu into a focal point for scientists. This past March, more than a hundred glacier researchers gathered for the Dagu Glacier International Academic Summit Forum near the mountain to share field reports, experiments, and a hard consensus: glaciers can’t be saved from melting — only slowed.

Most glacier research still focuses on how fast glaciers are shrinking, how much ice has vanished, and what dangers may follow. Some warn of floods and collapses, others stress what’s already lost.

A scientist presents research on the shrinking Rongbuk Glacier in Sichuan province, March 2025. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone

A presentation at the Dagu Glacier Forum calls for urgent action to protect glaciers, Sichuan province, March 2025. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone

The only real solution, scientists admit, lies in reducing carbon emissions, a global task beyond the reach of any single project.

Still, Wang and his team keep going. Their experimental methods rely on machines, materials, and electricity — all costly, and always in short supply. Dagu is one of the few glaciers where such efforts are even possible, thanks to tourist infrastructure and local funding.

For the moment, the white blankets and artificial snow are all they have, and there’s no clear next step. But Wang believes even a failed attempt is better than doing nothing.

“We’re just a few dozen scientists,” he says. “But if our work makes people care about glaciers, then it’s worth it.”

The visibly melting Dagu Glacier in Sichuan province. Xu Hui/The Paper

Vanishing point

On the slopes below, the signs of stress were visible well before the scientists arrived.

For Legden, a 48-year-old Tibetan herder, the shorter winters once seemed like good news. The grass came sooner, his yaks fattened more easily, and life felt a little less harsh. “Nowadays, we don’t even wear those thick winter coats anymore,” he says.

But he knows better now. “Obviously, it’s because of climate warming,” he adds in thickly accented Mandarin, using a phrase he picked up from the researchers who now pass through his village to study Dagu Glacier.

The glacier’s name comes from Tibetan and means “the glacier in the deep valley.” But Legden still remembers when it was simply called Snow Mountain — one of thousands of nameless peaks once draped in white.

Legden (center), a Tibetan herder turned scenic area worker, at the Dagu Glacier Scenic Area, Sichuan province, March 2025. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone

Unlike the towering continental ice sheets of Antarctica or Greenland, Dagu is an alpine glacier. It begins high in the Hengduan mountain range, where compacted snow stretches down like a ribbon of ice.

“When people studied it more closely, they identified it as a glacier. There were even photos — it was magnificent,” Legden recalls. “But in recent years, the ice has been melting faster and faster.”

When scientists later confirmed that Dagu could vanish within a decade, it left Legden and others in the village with a quiet unease. “We didn’t want it to be true,” he says.

But the more Dagu retreats, the more people come to see it. Since 2007, over a million tourists, both foreign and domestic, have made the trip, chasing snow, altitude, and the chance to witness something that might soon be gone.

The influx has transformed the local economy and brought rare visibility to a remote corner of Sichuan province. It also made Dagu one of the few glaciers in China with the roads, cable cars, and electricity needed to support scientific expeditions — including Wang’s experimental efforts to slow the melt.

Before the tourism boom, Legden’s village lived off the land — herding yaks, collecting caterpillar fungus, and digging for fritillaria roots used in traditional Chinese medicine.

That began to change in the early 2000s, when the Dagu Glacier Scenic Area was approved for development. By 2007, tourists had begun to arrive, and most locals picked up second jobs. For Legden, that meant patrolling the mountain, collecting litter, and watching for fires.

The cable car at the Dagu Glacier Scenic Area, Sichuan province, March 2025. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone

Today, he and his son both work for the scenic area. His wife stays home with the cattle. Their daughter is in university, set to graduate this June.

One of his newer tasks is helping install infrared cameras across the surrounding reserve. In 2020, one of the cameras he set up captured the first confirmed sighting of a snow leopard, a vulnerable species rarely seen in this part of Sichuan.

Through his work, he also began meeting more scientists, picking up unfamiliar terms: glacier, global warming, climate change. At first, they felt abstract, but then the valley began to shift.

Last July, days of torrential rain triggered mudslides across Heishui County, a five-hour drive northwest of the provincial capital Chengdu. A month later came an extreme heatwave never experienced before by locals. The glacier’s retreat didn’t cause either, but it no longer felt distant.

Yet, the buses keep coming.

From Heishui County, a one-hour ride into the mountains, followed by a 15-minute cable car, brings tourists to 4,860 meters — where Dagu Glacier comes into view: fractured, thinned, streaked with rock.

Atop a nearby peak, a tour group wandered around in bright Tibetan-style souvenir coats. One couple complained that they’d paid too much just to see a bit of snow.

Told that the glacier they were scheduled to visit might disappear within five years, the wife paused, then smiled. “Oh,” she said. “Then I guess we’re getting our money’s worth.”

Tourists in Heishui County ahead of the trek to Dagu Glacier, Sichuan province, March 2025. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone

Blankets and belief

With calls to act on climate change gaining little ground with the public, Wang Feiteng turned to other ways of reaching people.

“When you mention glaciers, many think of the poles. Or the Alps,” Wang tells Sixth Tone. “If you tell them China has more than 60,000, they’re shocked. ‘China? That many?’”

Over time, Wang began building a new vocabulary. He compared glaciers to cancer patients, and rising ice temperatures to a human fever.

Previously, he’d even push back when his work was described as “putting a blanket over a glacier,” but now, when schoolchildren visit, he leans into the metaphor — and explains why the blanket matters.

But before the metaphor, it was just another wild idea.

Borrowing a snow-preservation technique from ski resorts in Austria and Switzerland, Wang brought six rolls of white fabric to Dagu Glacier in 2020. He hoped that by covering part of the ice, he could slow its melt.

The principle is simple: Clean, reflective material reflects more sunlight than bare or dirt-covered ice, lowering the glacier’s surface temperature.

Wang’s team surveys glacier areas covered with geotextile fabric. Courtesy of Wang’s team

Across a 500-square-meter test patch on Dagu, Wang’s team laid six rolls of geotextile fabric — a synthetic, breathable material often used in construction and agriculture to regulate heat and moisture.

Each time, the team hauls the fabric up in July and unrolls it across the ice. Using drones and surveying tools, they scan the surface and set baseline measurements. By late August, they return to check for wind damage or shifting. And come October, they gather data to see whether the glacier held its ground.

They found that the covered ice lost 34% less volume than nearby exposed sections. Even a year after the fabric was removed, the patch melted 15% slower, owing to the extra ice it had retained.

In 2022, Wang took the same approach to glaciers in the Tian Mountains, located in Kyrgyzstan and China’s northwestern Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, with similarly promising results. That year, materials scientist Zhu Bin from Nanjing University refined the method further, replacing geotextile with a thin, highly reflective nanofilm. In a 200-meter test zone, it cut the melt rate by more than threefold.

“Many people say my research isn’t technical enough. I used to feel a bit wronged by that,” says Wang. “But I did what others were thinking about, talking about, but never really tried.”

Wang’s team takes measurements on the glacier. Courtesy of Xie Yida

In 2016, Wang was part of the team tasked with producing artificial snow for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics — a high-pressure assignment in a dry, low-snow region where natural snowfall couldn’t be counted on.

At the time, few in China had experience with snowmaking. Wang, already a glacier specialist with years of fieldwork behind him, became one of the first to apply that knowledge at scale.

Last year, he brought that expertise to Dagu Glacier. Field trials and model simulations suggested that, under the right conditions, artificial snow could help the glacier recover some mass.

In September, his team hauled a small snowmaking machine to the mountaintop and sprayed a bare patch of ice. But with temperatures hovering around 30 degrees Celsius, it was too warm for real snow to form.

An artificial snow machine used by Wang’s team atop Dagu Glacier, Sept. 4, 2024. Xu Hui/The Paper

The experiment briefly went viral online. For a moment, it looked like someone had found a way to stop the melt.

Wang knew better: the science might work, but the costs don’t. The fabric, the machines, the power — all of it adds up. And scaling the method to China’s tens of thousands of glaciers is another matter entirely.

Dagu is, in many ways, an outlier. Most glaciers in China are remote and difficult to reach. But Dagu sits at the center of a built-up tourist site, with electricity and year-round access to water. That infrastructure makes experimentation possible.

So does the funding: the blanket and snowmaking trials have been paid for almost entirely by tourism revenue.

But it’s a fragile trade-off. Tourism brings in money now, with the local government estimating that future annual revenue could reach 40 million yuan ($5.5 million) — only if the ice doesn’t vanish first.

And while geotextile fabric is cheap, it’s only modestly effective. Nanofilm works better, but at 350 yuan per square meter, covering even a double duvet’s worth of glacier costs more than 1,600 yuan. To blanket the glacier fully would take 140 million yuan a year. Artificial snow, under ideal conditions, would add another 30 million.

Footage shows researchers unrolling geotextile fabric atop Dagu Glacier as part of efforts to slow its melting. Courtesy of Wang’s team

For the local government, the glacier is still the main draw. So this past March, the day after the academic forum, local tourism officials met with scientists behind closed doors.

The meeting felt less like a strategy session than a last-ditch consultation. Scientists laid out a string of proposals: smarter monitoring systems, restricted access zones, core drilling to preserve data, a volunteer program, even letting tourists “adopt” parts of the glacier — a nod to popular carbon offset schemes like the Alibaba-backed Ant Forest, in which Alipay users are gifted points for low-carbon behaviors that can then be converted into real trees planted by the company.

But the biggest questions remained unanswered: Would any of it work? And who would pay for it?

Some local officials have also begun rethinking how they present the glacier to the public. Instead of hiding its decline, they’re now considering whether its vulnerability could become the draw.

“I used to worry that talking about ‘glacier protection’ would scare off visitors,” explains Wang Gang, director of the Dagu Glacier Management Bureau. “That it would mean cutting back development. But after hearing the experts, I realized this isn’t just about human activity. It’s climate. It’s bigger than us. And we can’t stop it.”

En route to the Dagu Glacier Scenic Area, Sichuan province, March 2025. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone

Cold truth

Wang Gang’s epiphany echoed a consensus long familiar to the hundred scientists who gathered at the Dagu Glacier International Academic Summit Forum in March to share research on glacier preservation.

“I’ve been here for six years,” says Xie Yida, Wang’s Ph.D. student and the lead author of the papers on glacier blanketing and artificial snowmaking on Dagu. “At first, the research felt exciting. We were doing things no one else had tried. But later, the more I thought about it, the more powerless I felt.”

Each of Xie’s papers ends with the same disclaimer: the methods only worked on accessible, well-funded glaciers like Dagu. “In the end,” he admits, “the conclusion is always the same: we need to reduce emissions. We have to rely on a collective sense of responsibility.”

Xie Yida, Wang’s Ph.D. student, at the Dagu Glacier, Sichuan province, March 2025. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone

A marker noting location and altitude on Dagu Glacier, Sichuan province, March 2025. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone

He often returns to a quote from geologist and vice chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, Ding Zhongli: “This isn’t about saving the Earth. It’s about saving ourselves.”

“Right now, no one really feels it,” Xie said. “Because the melting glaciers haven’t yet threatened the survival of all humanity.”

Over the long term, the consequences are enormous.

Glaciers store around 70% of the world’s freshwater. By 2100, more than 80% of them could disappear. In China alone, the glaciers in the country’s mountainous west hold the equivalent of four Yangtze Rivers’ worth of water. Their uneven retreat could trigger landslides, floods, and other disasters. Rising seas will push into low-lying coasts, threatening nearly 680 million people worldwide.

“It’s incredibly hard for humans to fight nature,” says Xie. “Everyone talks about investing money, but how much money is enough to protect a glacier?”

Outside the forum’s formal sessions, glacier researchers spoke about the limits of their work: how hard it was to produce results, how that made funding scarce, and how it drove younger scientists out of the field. Some pointed to global politics — the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, and countries blaming each other instead of cutting emissions.

“The feeling of powerlessness is the norm,” one said.

Scientists watch a presentation at the Dagu Glacier Scenic Area, Sichuan province, March 2025. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone

Like many at the forum, Wang had felt it too. So when results proved hard to deliver, and progress harder to scale, he shifted his focus. Raising public awareness, he decided, was a result in itself.

“At least I did something,” he says. “And if this experiment can get society to pay attention to glaciers, that’s enough for me.”

Still, nothing has stopped the melt.

When Wang first began his work, more than 90% of Dagu had already vanished. From 5.3 square kilometers in the 1960s to just 0.0316 in 2024, its ice has splintered into scattered remnants. In the last four years, the terminus retreated by another 20 meters.

At a high-altitude observation platform, Xie Yida points toward a snow-covered slope in the distance. “That’s where we’re running the experiment,” he says. From here, nothing is visible.

A tourist poses next to a stone reading “Challenge Yourself — 4,860m” at the Dagu Glacier Scenic Area in Sichuan province, March 2025. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone

He gathers the other scientists for a photo beside a stone etched with the words: Challenge Yourself — 4,860m. Around them, tourists inhale from portable oxygen canisters. Xie doesn’t need one.

Before leaving Dagu, scientists attending the forum were handed balloons, each bearing the name of a dying glacier somewhere around the world. Together, they let them go — bright dots rising into the mountain air.

After long discussions on how to sound the alarm, they could only hope the message would land. (SIXTH TONE)

Scientists attending the Dagu Glacier Forum are handed balloons bearing the names of dying glaciers before a symbolic release, Sichuan province, March 2025. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone

The balloons rise into the sky at the close of the Dagu Glacier Forum, Sichuan province, March 2025. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone

Appendix